In 1971 I was just out of college and had moved to Eugene, Oregon, “running capital of the world,” to run. As an undergrad at the University of Hawaii I had won several state track titles, but had been significantly hampered by injuries, and I still wanted to see how good I could become.

It was Bill Bowerman’s last year as the University of Oregon coach, and the next year he would be the U.S. Olympic coach and founded Nike.

Consistent with my history I soon was injured in Oregon, this time with a heel spur/plantar fasciitis. Two Olympians, Steve Prefontaine (5K) and Mike Manley (steeplechase) showed me how to tape my foot which immediately got better, and surprisingly, my hip pointer (pain at the top of my pelvic bone) also went away. At the time I didn’t see the full significance of this, but it did start me thinking about how my foot, my foundation, affected the rest of my body.

I have come to recognize that most aches and pains are related to biomechanics. In this article I discuss what you can do about avoiding injuries, and especially about the foot’s role in avoiding them, the flip side of injury being efficient mechanics.

Two main ingredients make up mechanical health: good posture, and moving in a full connected way from the center of your body. A third, variety, helps you achieve the first two.

At a recent convention, the hot discussion was whether good foot posture, or good pelvic posture, was more important. That’s like asking, is it better to drink water or eat food? Good posture includes the whole body.

Nevertheless, I focus on footbeds/orthotics that address the foot’s posture, a “necessary and not sufficient” part of the puzzle, and leave the rest to people like Anthony.

The foot is your base of support, and in order to be balanced, the foot must be balanced. Imagine building a house on an unstable foundation.

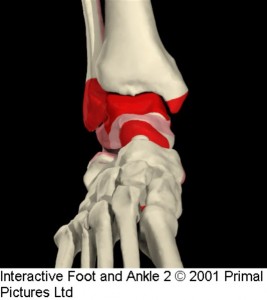

Although the foot is of particular importance, it is also uniquely difficult to balance because many of the foot’s bones are horizontal. While you can stack/nicely balance/ the bones in the rest of the body on top of one another, you cannot do that with the feet. In order to maintain their arch shape, the bones must be tightly held together, or the foot will collapse.

There are several soft tissue structures, namely the muscles, fascia and ligaments, which might do this.

Muscles can usually hold the arch up for a short time when you’re standing still and the forces are small. For example, if you weigh 100 pounds, the force on each foot is 50 pounds. It gets tougher when you walk however, when forces increase to 120 pounds, and extraordinarily more difficult when you run and the forces are 350 pounds. The bottom line is that muscles are not up to the task of providing good foot posture when you either stand for a longer period of time, or run. Indeed, muscles are designed to control and cause motion, and not be so involved in posture. If they do become too involved in posture, they become tight and sore.

Among the more common muscles that become tight from holding up the arch are the two hip flexors (Psoas major, Iliacus) and the Piriformis. Although they are external rotators, with the foot on the ground they lift up the arch. Tight hip flexors are associated with low back pain, and a tight Piriformis is associated with sciatic pain.

Fascia and ligaments are designed for postural support. It is their job to hold the arch up.

Fascia has the mechanical characteristic of being “plastic,” meaning that it adapts over time to what you ask it to do. Fascia is everywhere (the gristle in meat), and although it can support you in good posture, it often gets stuck supporting you in a hunched-over posture, making standing up straight more difficult. Typically it takes several months to change the length of fascia so that one day you might say “wow, standing up straight is not so difficult.”

Ligaments hold bones together, allowing movement while supporting structure. Their job is to limit joint distention and they become injured if stretched beyond a narrow range. Unlike muscles which actively contract, ligaments merely react to stretch, returning to their original position.

Because of their poor blood supply, ligaments are difficult to heal, which is why when you hurt your ankle, you often hope you break a bone, rather than stretch a ligament. Bones heal, often becoming stronger than they were originally, whereas stretched ligaments often remain longer, leaving you with a less stable joint.

When slowly stretched, as occurs over time, ligaments also become longer. When foot ligaments are longer, arches are flatter and your foundation is less aligned.

You might have inherited longer ligaments, or over time you might have lengthened your ligaments by exposing your foot to flat, hard surfaces. Since the foot adapts to the surface upon which you place it, by walking or running barefoot (or in minimalist shoes with no support), on a flat hard surface, you are asking your foot to become flatter. Our feet are not designed to function on these man-made surfaces, rather they are designed for randomly challenging, softer, supportive surfaces like pine needle covered forest paths strewn with rocks and roots; these surfaces keep your feet healthy.

The exception is if you have inherited longer ligaments and a flatter foot, in which case even the best environment won’t keep you healthy.

The consequence of a flatter foot, one that has poor posture, is the greater likelihood of many injuries, including injuries to the foot itself such as bunions, neuromas, plantar fasciitis and heel spurs, as well as to the Achilles, calf, shin, knee, groin, hip and low back. The ubiquitous plantar fasciitis, for example, is associated with excessive pulling on the plantar fascia (when the foot flattens, it also lengthens). There are many reasons behind this, including a tight calf and a rotated pelvis, but usually the primary risk factor is longer ligaments.

In that case it becomes necessary to complement the ligaments with a footbed that holds up the arch, creating good foot posture, which allows the muscles to do what they are designed to do, which is to move your body. How important the footbed is will depend on how misaligned you are without it. The longer your ligaments, the more misaligned you are, and the more time you want to spend being supported by a footbed.

Of course it is also important to deal with the other risk factors such as the problematic calf and pelvis; however that is not so much my business, nor is it the subject of this article.

I was also asked to comment on minimalist shoes, such as the Vibram five finger shoe, since they are somewhat the rage these days.

Under no circumstances that I can think of, will your feet be healthy if you walk or run barefoot for any period of time on man-made hard, flat surfaces. This includes minimalist shoes, which allow you to function as if you were barefoot.

I agree that shoes have become too cushioned and insulate us from our environment. Nevertheless, some of us tried the experiment of minimalist shoes back in the late ‘60s, when we used to run in black canvas Keds with a minimalist crepe rubber sole. Our feet lost some of their arch and spring, and we are suffering from that abuse today.

Of course, at the time we had young bodies, didn’t know any better, and loved our Keds. But I also remember my excitement in the early ’70s when I wore my first cushioned shoe, a Tiger (now Asics) Cortez, designed to compensate for the hard roads. Intuitively I sensed that the hardness of roads was part of the problem.

You will be able to run successfully in a minimalist shoe if you stick to softer, supportive, randomly changing surfaces, and if you have inherited sufficiently strong ligaments to maintain good foot posture. Otherwise, you’re asking for trouble.

I am also occasionally asked if footbeds make your muscles lazy. After reading this, you will realize the answer is no. Footbeds complement ligaments to achieve good posture. They don’t do the work of muscles. On the contrary, good foot posture allows the muscles to work in a more balanced, efficient way.

Doug Stewart, Ph.D. (biomechanics), went to college on a track scholarship, often trying to run 100 miles a week, and often getting injured. His injuries and a desire to be more efficient motivated him to address his mechanics, which as it turns out are human mechanics, and common to most of us☺. He makes footbeds, and can be reached for comments by emailing Dougstewart2@cox.net.

Tags: biomechanics, Doug Stewart, feet, footbed, Vibrams

Thanks for sharing this Anthony. Dr Stewart’s comments also make sense as nowadays everyone is flooded with marketing claims, “scientific data”, etc… at uni, my stats lecturer said “Statistics don’t lie… statisticians do” lol…

Dr Stewart’s “run in black canvas Keds with a minimalist crepe rubber sole..” rings a familiar bell… in many government (non-private) schools in Malaysia, we have to wear canvas shoes the whole day even for sports. So we would be running in the field using shoes that have a thin rubber sole, or sometimes run on the tarmac roads… if you’re a school athlete, then you get to wear spikes or proper sports shoes. Well, all the years of pounding on minimalist shoes can take a toll and in my case i have inherited flat feet, so the lack of shoe cushioning had some effect i think…

Anyway, I’m now glad to have found negative heel shoes n wear Springboost at the office…

thanks again for sharing your insights!

I love my vibram 5 fingers shoes, though I’m a yogini, not a runner. I wear them walking, riding a bike, have stomped out a small fire with them on, worn them in the ocean, and as daily wear shoes. I agree that pavement is not the way to go for anyone who is running.

I am replying because I used to have “flat feet” and was in arch supports my entire childhood and teenage-hood, until I discovered through training in biomechanical yoga, that I could strengthen the arch and rebalance the foot, which of course does involve balancing the whole posture from the ground up, not just the feet. My arches are now awesome! Years of wearing arch supports only supported my flat arches; years of therapeutic yoga has strengthened and un-flattened them. Most yoga classes do not go into anywhere near this kind of detail, but there are a few yoga professionals like me out there who are working successfully with the body in these subtle ways. My client asks me, “why didn’t my physical therapist teach me this?” That’s a tough question to answer.

Again, I am not a runner and can’t vote for or against vibrams for serious running. But I can vote for acknowledging the power of our subtle understanding to give us more skill in action.

Thanks Anthony for sharing this. I can’t tell you enough just how much I have learned from you.

I have attended many of your lectures at IDEA and was thrilled to see you at the Low Back Congress in LA.

You have helped me become a great teacher.

Thanks again.

Great to see discussion surrounding the relationship between pelvic position and the feet – because in the prevailing medical/ mechanistic view of the body this relationship is all but ignored. Perhaps though I would be cautious to assert that ‘it takes months to change the lenght of fascia’ -as isn’t this one of the great benefits of fascial release techiniques with massage, the franklin method etc etc. The right corrective exercises focusing on the entire fascial link from the pelvis to the feet can have enourmous benefits to ‘good foot posture’ – prior to introducing orthotics. Besides we don’t recommend someone wear a ‘weight training belt’ because their pelvic and lumbar stabilises aren’t working with correct biomechanics.

Brendan Rigby

Brendan Rigby

Doug’s Response to Christy

FYI, Five Finger shoes have very thin soles, minimal support and are cut for your individual toes, like a glove.

Based on past experience, I suspect that many health professionals who read my recent article, Life’s Balancing Act, agree with Christy. She wrote that she successfully holds up her arches with muscles while walking in her five finger shoes, on surfaces that presumably are primarily hard and flat. This follow-up addresses why I believe such an approach may lead to problems.

First, let’s address what “functional training” means, since it’s an important concept that’s on everybody’s mind.

To me, functional training means figuring out how the body is designed to function, which implies efficiency, and then encouraging it to do so. The implication of course is that being barefooted or in minimalist shoes, is ‘functional.’

To understand functional training, you have to understand the different components that make up the body, and how they fit together. I’m going to argue why going barefooted is not always functional.

Certainly I like the idea that we’re getting away from thick, squishy shoes that have become too much the norm. I’m also pleased that we have minimalist shoes like the Vibram five fingers, that allow us to walk more like we’re barefoot. Going barefoot can be functional, but only if we have strong, supportive foot ligaments, and walk on randomly changing, usually softer surfaces.

I agree that muscles should be involved in supporting your arches, but should not be the primary support. Further, their task is to control and create motion, rather than hold up the arch in a somewhat static position.

Ligaments, fascia and contoured ground are designed to provide such static support. Muscles are active, designed for motion, whereas ligaments are passive, designed to hold things in place.

Moreover, Christy had flat feet when she was younger, which means that she inherited ligaments that did not adequately support her feet, and she currently walks on flat ground, which also does not support her feet. Both of these things, one due to her genetics and the other to her environment, mean that in order to have good foot posture, she either will have to have some form of external support like a footbed, or her muscles will do more than their share of the work.

Exacerbating the problem of man-made surfaces is that they are very consistent. Not only are muscles designed to control and cause motion, they are also designed to do it in a randomly changing, stress/rest pattern; a pattern found in nature, not on man-made surfaces.

Let’s examine how Christy is able to intentionally support her arches with her muscles, and at what cost, and why this might not be doable for many of us.

Her Lifestyle: Christy appears to lead a quiet lifestyle, well within her physical capabilities, so that forces under her feet are relatively small. This makes it easier to hold up her arch, and in the short run makes it less likely that she will be injured from having poor foot posture. Further, it has been my experience that when people are asked to hold up their arches to demonstrate good posture, for example in yoga or Pilates, they do so when they are standing, when the forces on each foot are half their body weight, again a relatively small force compared to walking or running.

She wears five finger shoes, acknowledging that running on pavement is “not the way to go,” but implying that walking on pavement is okay. She suggests she is able to overcome the foot’s design to adapt to the ground, by using her muscles so that the foot will not adapt to those flat surfaces.

A disadvantage of using muscles in this quasi-static way for any period of time, is that they become tight and sore. To deal with the consequences, she does a lot of yoga. The less efficiently (and I would say functionally) you do something, the more time and effort you must spend to counteract the inefficiency. Christy may enjoy doing a lot of yoga everyday, so this may be a moderately satisfactory solution for her.

However, a separate issue, and a disadvantage that is not addressed with yoga, is that if you don’t expose yourself to high, intermittent physical stress (a good idea in general), your bones are at greater risk of becoming osteoporotic. In fact, it appears that running 30 to 40 steps per day may be necessary in order to have healthy bones.

Her background growing up:

Through the end of her teenage growth years Christy wore arch supports. One of the few times that you may be able to shorten ligaments is when you are growing. Although she started out with “flat feet,” her arch supports presumably created good foot posture, allowing the ligaments to perhaps grow closer to a healthy foot shape. I argue that if you do this, you may need less external support once you have finished growing, as an adult.

In addition, fascia changes its length at any time in your life. By holding up your arches with either ligaments, a footbed/arch support, softer contoured ground or your muscles, fascia will shorten to contribute to holding up the arches.

The same is true for muscles, they become longer or shorter, and stronger or weaker according to how you train them. Thus, muscles can also successfully contribute to holding up the arches.

As a result, because of more supportive ligaments, fascia, and muscles, it is easier for Christy as an adult to hold up her arches with muscles.

[By the way, a somewhat comparable thing happens to a mother during pregnancy. If she wears footbeds while pregnant, her ligaments will not lengthen as much during her pregnancy, so that once the baby has been delivered and the relaxin hormone has left her body, she will have similar length ligaments (and a similar arch) as she had pre-pregnancy. Otherwise, allowed to adapt to a flat floor, her foot will be flatter, and ¼-½ size larger.]

Let’s examine why walking barefoot (or in minimalist shoes) for any period of time on hard flat surfaces is not healthy, under any circumstances.

Feet are designed for generally softer, challenging, randomly changing surfaces. Wheels are designed for hard flat surfaces. Almost nowhere in our evolutionary past or in nature today, do you see surfaces like roads or flat floors.

1. That our feet are able to adapt to uneven ground makes us more stable, and is an evolutionary advantage. This greater stability makes us more able to run, hunt, carry water etc. on uneven ground. Imagine if our feet were flat and immobile; when we stepped on a rock our feet would act like a teeter totter, and we would sprain our ankle. Nevertheless, our feet are not flat and immobile, instead they are designed to adapt to the surface upon which we place them, and the surface for which our feet are designed, is a softer, uneven, randomly changing one.

2. The fact that the ground adapts to our feet (notice your footprint), and supports us, means that we don’t have to work as hard. Your feet and ground share the work, they each adapt to the other.

However, your foot will flatten on a flat, hard surface, doing all of the adapting, unless held up by structures within the body, like ligaments, fascia and muscles. Under these conditions you are asking your internal structures to repetitiously work against/overcome what the foot is trying to do, which is to flatten.

Moreover, by themselves muscles are usually not capable of maintaining the arch, particularly as you get closer to your body’s limits. Even ligaments, as strong and resilient as they are, when repeatedly exposed to a flat surface, will tend to lengthen over time. And fascia will adapt to whatever you do enough of, so if your foot flattens a little, the fascia will lengthen a little to accommodate that flatter foot, then providing less postural support.

The consequences of having a foot that is not well aligned (too flat) includes bunions, neuromas, plantar fasciitis, Achilles problems, shin splints, knee problems, groin injuries, hip replacements, low back disc degeneration.

Typically muscles that become too tight as a result of attempting to support against poor foot posture, are those in your feet and shin, including the Tibialis Anterior and Posterior, as well as those around your knee, hip and low back. And what about the muscles that are stretched, like the groin? Is this a Catch-22, that we use our muscles to hold up the arches, and then have to do a lot of yoga to counteract using them in such a way? Even then, most of us cannot do enough exercise to be successful (check out how many people in yoga class have bunions).

In addition, tight muscles constrain full gracious movement, and in the end, it is movement that keeps us healthy.

Certainly the random movements that Christy does by walking in the ocean, etc. are useful, and the yoga also. These kinds of activities almost always make you healthier, if done in moderation, and are to be included. They are not, however, exclusive.

You want to have good posture as a result of strong ligaments, complemented with footbeds if necessary. Also walk on softer (thick grasses, sand, degraded earth), supportive (rocks and roots), changing surfaces in order to move fully and easily. You might have figured out that you can’t put a full-length footbed in a five finger shoe, so if you wear a footbed, put it in a thin-soled shoe, like a skateboard shoe, which I recommend to almost all of my clients. Such a shoe is stable on a flat hard man-made surface, and allows your foot to move on a rocky, randomly changing natural one, both desirable characteristics.

Christy and I agree that arches are useful, but some experts disagree. Let’s examine why good arches support mechanical health, and you can make up your own mind.

1. Arches create good foot posture, which in turn facilitates better whole body posture, allowing you to move in a more balanced way.

2. Arches provide strength while allowing the foot to be made out of lightweight materials. Since your foot is at the end of a long pendulum, being lightweight is a considerable advantage.

3. Arches help absorb impact, storing some of that energy and giving it back when you push off.

4. Arches help you adapt to healthy uneven terrain.

To me, these functions are obvious and important. Nevertheless I recently read an article in the New York Times (see reference below from 1/17/11), in which a well-known researcher was quoted as saying that “because we don’t grip trees with our feet anymore, we don’t really need an arch. Thus a flatfoot is not something that is bad per se.”

I hope you now see why a healthy arch is integral to good posture and gracious movement, and you have a better idea of how to achieve it.

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/18/health/nutrition/18best.html?_r=1&scp=1&sq=gina%20kolata%20orthotics&st=cse